Mapping indicator species in an intertidal zone

“I don't know if you've heard this, but the Californian coast is experiencing a lot of environmental challenges right now including a severe die off of kelp, sea stars, and other species. It's starting to look like another one of those environmental disaster stories,” says Warren ‘Waz’ Hewerdine.

A trained geomatic engineer, Hewerdine wears many hats as a photographer, drone operator and citizen scientist volunteering with the California Academy of Sciences and the Greater Farallones Association’s LiMPETS program, lending his skills to help monitor the area and better understand the impacts of a changing climate.

“The LiMPETS program takes students - school kids - into intertidal zones to do data collection, species counts and coverage assessment,” explains Hewerdine. “All that goes into a huge database to monitor the change of species coverage in the intertidal zones over an extended period of time.”

“I asked the organisers, what would happen if we got some aerial imagery and created an orthomosaic map? What could they use that for?”

Project details

| Location | California, USA |

| Institutions | California Academy of Sciences Greater Farallones Association LiMPETS |

| Drone operator | Warren ‘Waz’ Hewerdine |

| Hardware | DJI Phantom 4 Pro |

| Software | Pix4Dcapture Pix4Dmapper Pix4Dcloud |

| Survey area | 13 acres |

| Focus area | 5 x 10 meters |

| Images | 600 per flight |

| Processing time | 50 minutes |

| Output | Orthomosaic |

| GSD | 0.8cm |

Mapping a fragile ecosystem

Both the California Academy of Sciences and the Greater Farallones Association saw the potential of drone mapping. “Straight away, they said it was a fantastic idea,” says Hewerdine, adding: “They’ve tried other things in the past. They've even attached a camera to a kite and flown it above the study area.”

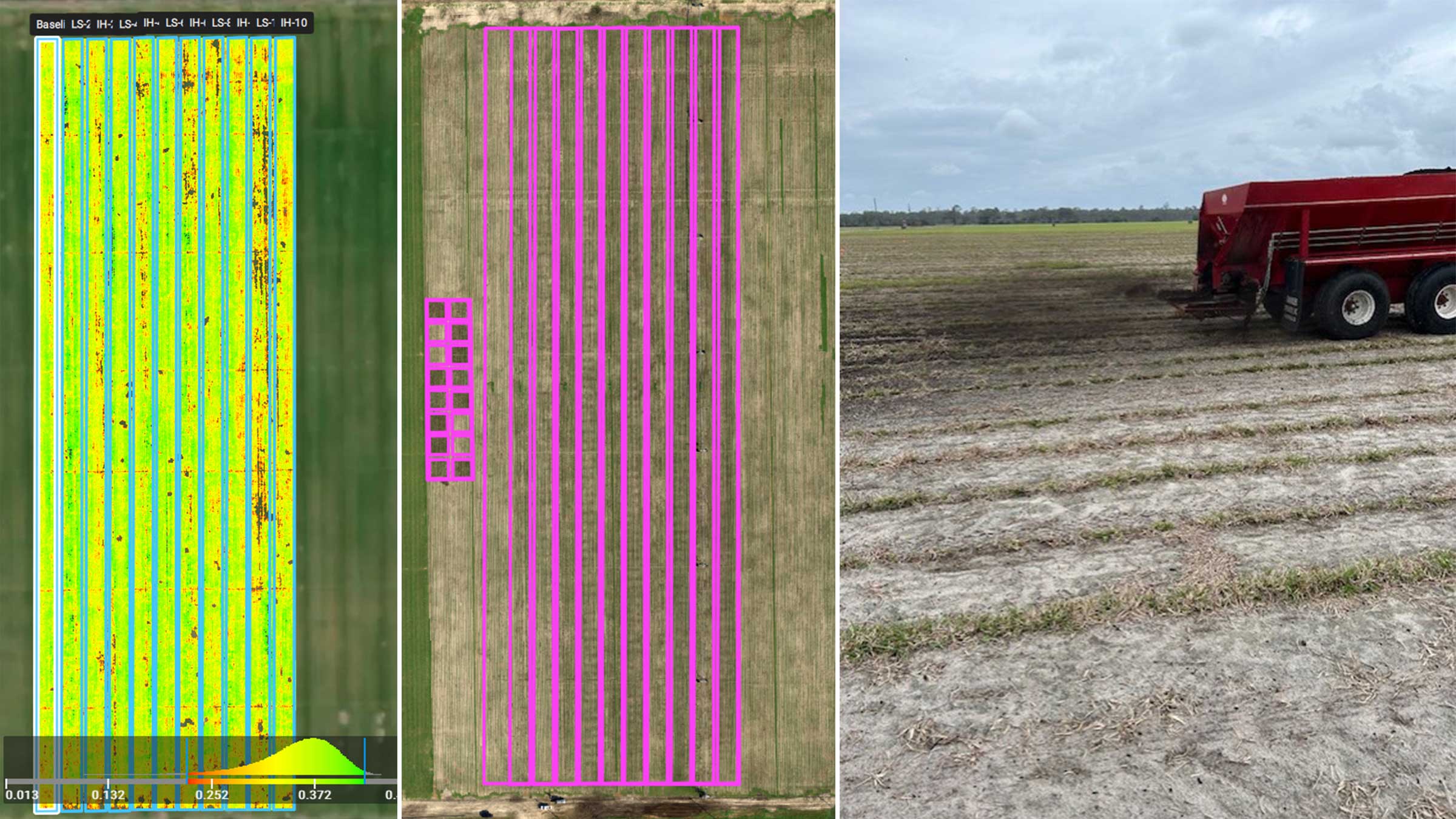

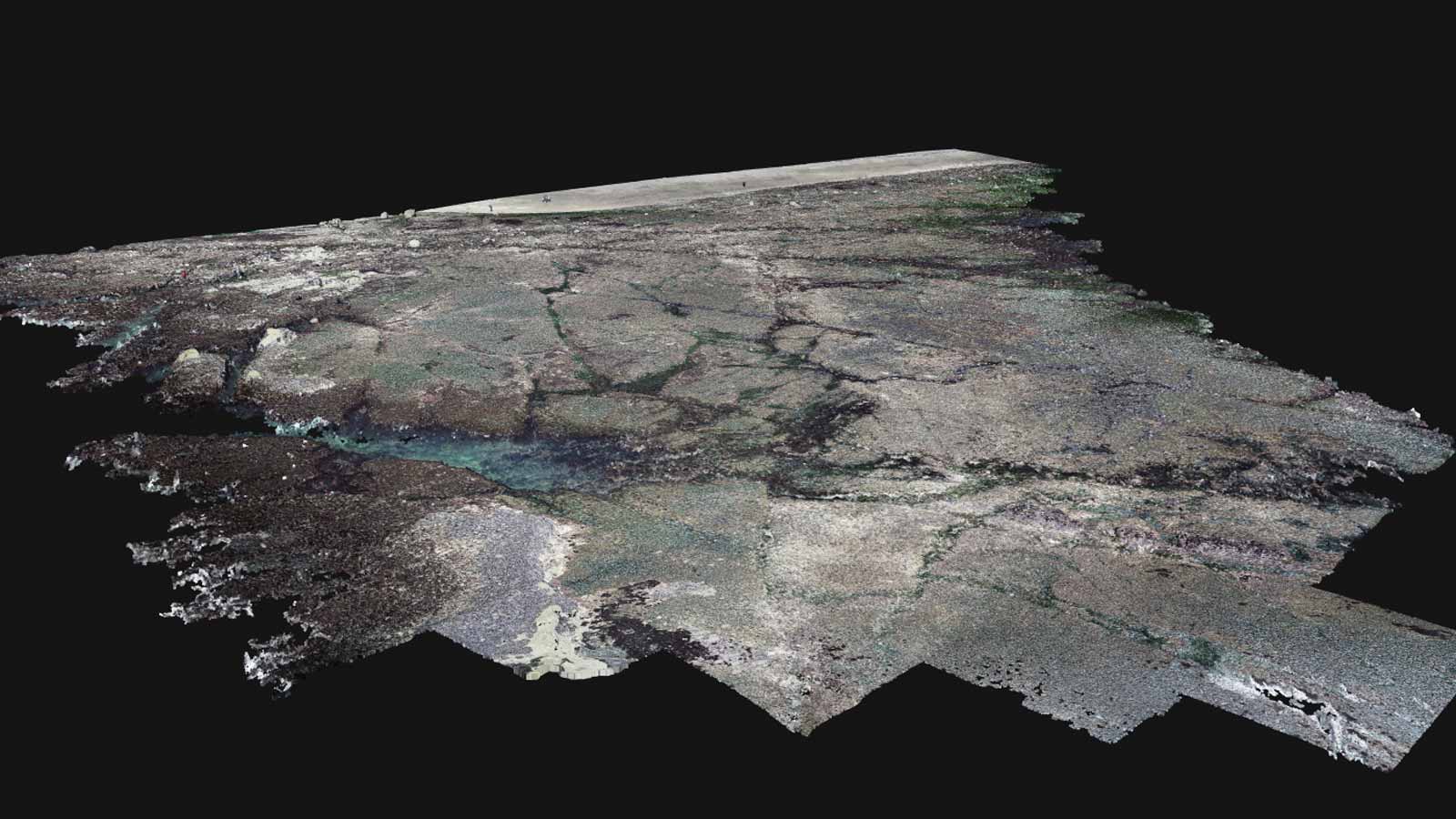

With more sophisticated hardware, Hewerdine was able to create a test map very quickly. Upon seeing the data, both institutions saw the value of tracking mussel beds and algae cover in different locations along the coast.

Mussels as an indicator species

California mussels are more precisely known as Mytilus californianus, and can be spotted in intertidal zones along the coast of the eastern Pacific Ocean, from southern Baja California, Mexico, and to south eastern Alaska - or steamed with white wine and butter.

The tasty molluscs are an indicator species. Like the idiomatic ‘canary in a coalmine’ the health of indicator species, or ‘bioindicator,’ can highlight wider problems.

Mussels are filter feeders who subsist on microorganisms and are susceptible to pollution. As such, when mussels beds fail to thrive, it’s a clear indicator that the wider environment is struggling.

In addition to mussels, the institutes are interested in gaining an overview of the coastline in general. The eventual goal is a “highly detailed, ongoing database of how these places look and how they change over time from any external influence,” says Hewerdine.

With the right data, changes caused by boats grounding, mussel harvests, water runoff and more can be tracked and quantified. The areas of interest are both in and out of a state park, giving the organizations the chance to compare the differences between protected and non-protected areas.

While the current study area is small, it’s hoped that findings can be extrapolated to other areas along the coast - and that the study can be extended.

Intertidal challenges

An intertidal zone is just what it sounds like: the area of the coast which is submerged at high tide, and exposed at low tide. The regular, rapid changes make it an interesting area for scientific study.

The study examined two different beaches. The California Academy of Sciences focused on Pillar Point, a non-protected publicly accessible beach. The intertidal zone is a rock shelf extending out into the ocean, and the mussel beds are well known to the locals: “People are allowed to harvest there, and even as I was trying to map the area, people were coming with buckets and crowbars and picking off mussels!” says Hewerdine.

The LiMPETS narrowed their focus to Shell Beach, a couple of hours drive away further up the coast. The mussel beds at Shell Beach are located in the National Marine Sanctuaries, but the coastline is rugged, and more exposed than Pillar Point.

Despite the differences and the distance between the two study locations, they have a lot in common.

“Unfortunately, you can’t just flip a switch and make the tide go out,” bemoans Hewerdine. “So our mapping has to be on days with very, very low tides. A lot of the time, these tides are very early in the morning or at night, so you have to wait a long time to get good measurements.”

Tides leave a narrow window for citizen scientists like Hewerdine, who can count on about two hours before the tide starts coming back in “and you’re swimming.”

Adding to the challenge is California’s distinctive coastal weather (“Renowned for fog,” says Hewerdine).

The final challenge to be overcome involved paperwork. Pillar Point is close to Half Moon Bay Airport and an airforce military base, while Shell Beach is in a state park and a National Marine Sanctuary. Before taking off, “there was a lot to do from a permit perspective,” says Hewerdine.

Once all the permits were in place, flying was straight forward: Hewerdine used the free Pix4Dcapture app to control the drone and flew the sites manually. He took around 600 photos over the 13 acre site and 5 x 10 meter focus area, admitting in his concern about not capturing enough data, he may have ended up with more than was strictly required.

Delivering accurate results

With a background in geomatics engineering, Hewerdine was trained to use analytical stereoplotters to achieve a result that, Pix4Dmapper photogrammetry software, can deliver in a fraction of the time. After uploading the 600-odd images to Pix4Dcloud, the models took less than an hour to process.

Pix4Dcloud offers a quick and practical way for results to be processed with standard settings and shared with a simple link.

Hewerdine appreciates the ease of use. “Super technical, highly difficult, very expensive photogrammetry technology has always been difficult to access in the past,” he says. “And Pix4D is putting it in the hands of people like myself, to be able to bring it to organisations who would otherwise not be able to access it.”

The organizations were more than happy with the results. “I was really happy to hear how excited they were when they saw the visuals,” says Hewerdine.

With a GSD of just 0.8cm, the results are good - “But I think there is room to improve,” Hewerdine adds, mentioning the possibility of hand-carrying the drone over the mussel beds for an even better image.

An archive and an action plan

The maps and models are archived in the databases of the institutions where they can be referred to over the coming months and years as a permanent snapshot of this moment in time.

They are also a call to action for the volunteers who preserve the coastline.

Hewerdine comments that “People respond if they can see it’s going on,” and plans to use the footage in the institutions marketing plan to get people more involved. “Maybe we put together a timelapse over an extremely extended period time to communicate the change… I might be old and grey and sitting in my rocking chair by the time we gather enough footage. Anyway, I hope that’s the case, and the climate is changing that slowly.”As well as being passionate about the California coastline, Hewerdine is passionate about drone mapping. He explains: “If you’re doing something that makes the hair stand up on the back of the neck when you’re talking about it, you’re doing something right. This is something that does that, and hopefully we can expand it to be a much larger program.”

He adds: “Especially now, in the highly variable, environmental catastrophe that we’re facing, the more we can do, and the more data we can collect, that can only result in something good.”