Images to action: mapping the Santa Rosa fire storms

Unfortunately, in the space of a few days, the fires burned tens of thousands of acres.

One particularly hard-hit area was in and around the city of Santa Rosa, where over 34,000 acres, much of it residential, was turned to ash. When natural and manmade disasters happen, emergency responders look to individuals like Commander Tom Madigan, a 20-year law enforcement veteran in the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office, and his team to gather information as quickly as possible to support disaster response and recovery activities.

Madigan oversees the organization’s small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS) program. As part of the Santa Rosa disaster response, Madigan received an emergency a temporary flight restriction (TFR) Certificate of Authorization (CoA) from the Federal Aviation Administration. The emergency CoA allowed Madigan to gather data with the department’s growing fleet of drones.

After a quick survey of the damage, Madigan looked for help from professional UAV mapper, Greg Crutsinger of Scholar Farms and his data mapping post-processing solutions.

Ground zero

While fires continued to burn, Madigan, his team and Crutsinger’s first stop was the Journey’s End Mobile Park, an age-restricted mobile home community in Santa Rosa, where two residents died during the fires.

With one of the department’s DJI Phantom 4 drones equipped with 12-megapixel cameras, the team was able to map the mobile community quickly. After about 90 minutes of processing with Pix4Dmapper, professional photogrammetry software purpose-built for post-processing drone-gathered data, Crutsinger presented high resolution 2D and 3D models of the site to Madigan.

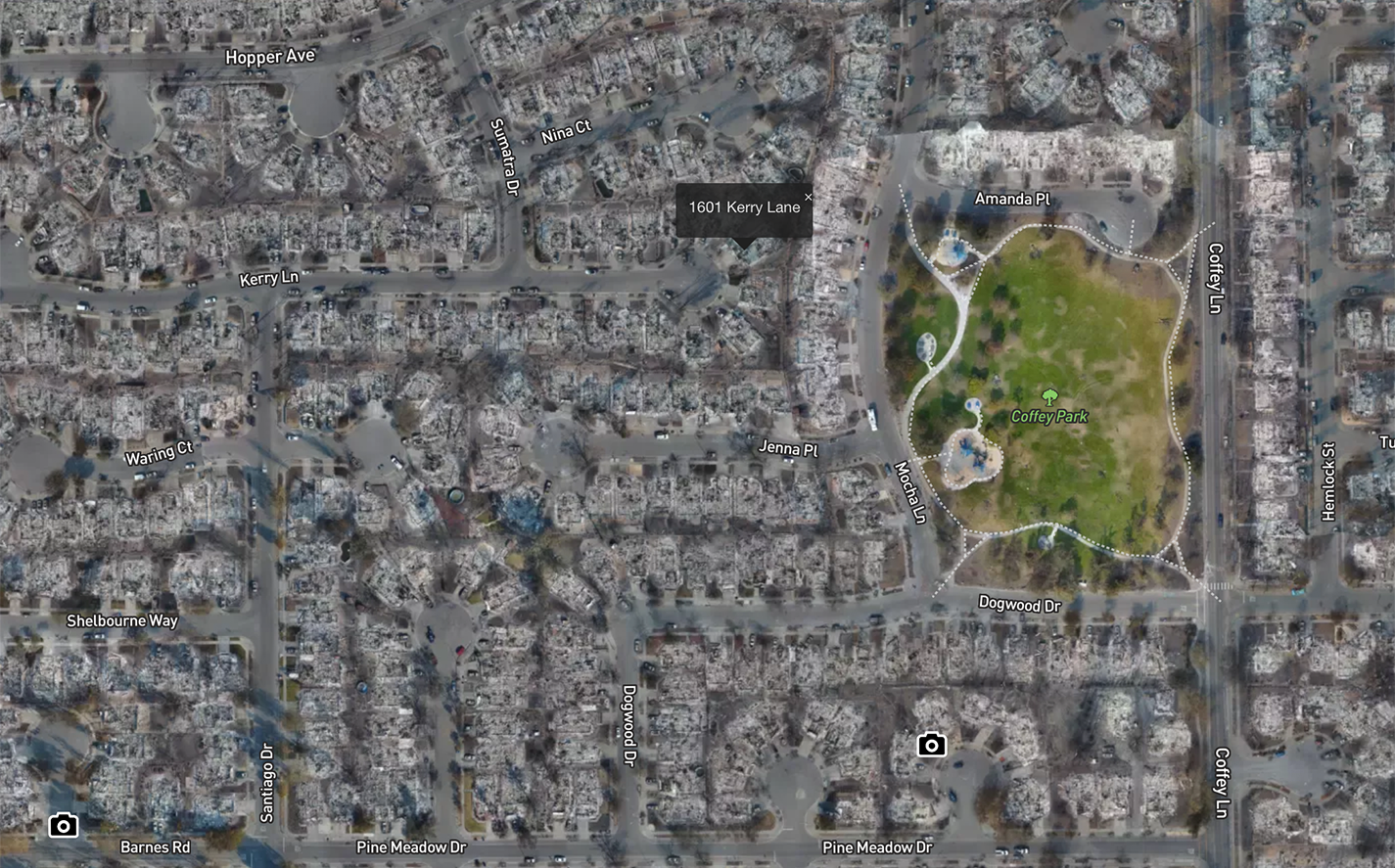

The next stop was Coffey Park, a suburban neighborhood where 3,500 homes were burned to the ground.

Mapping the burned area

The Coffey Park scene was considerably worse in terms of scope and scale than the mobile home park. Much of the 1.2 square kilometers neighborhood was just gray ash.

Madigan recalls, “We needed a map that would help coordinate first responders and set perimeters. Our first focus was to ensure that when residents returned to the burn area, there was no chance of injury. As well, the maps would help residents see the extent of damage to their homes and property.”

The team once again looked to the department’s fleet of DJI Phantom 4 drones equipped with 12-megapixel cameras—all the while staying well away from the many manned aircraft, such as Cal Fire helicopters, working in the area.

Crutsinger says, “The drones were limited to 100 ft flight altitude and we had to land immediately if other aircraft entered the area. The height restriction meant that we had to run many more drone flights to cover the large area.”

Typically, Crutsinger would map a landscape at around 400 ft. Flying four times lower than normal meant it would take the team four times as long to get the job done and require four times as many photos. As part of the Coffey Park team, Crutsinger’s job was to direct the drone routes to best capture photo overlaps of the park.

The process was straightforward, though tedious: Crutsinger would manually load a mission to one drone, hand it off to an officer fly and then move to the next mission using a Google map on his phone. Ultimately, it would take about two dozen flights (and as many batteries) to map the Coffey Park neighborhood. The team also collected panoramic images of the neighborhood, a process that took only a few hours, compared to a more traditional approach that would have taken days of walking the neighborhood with a camera or scanner.Once gathered, the data was transferred from the UAV storage devices to Crutsinger’s laptop, which was running on a generator. It was an immense effort by the team with dozens of flights and drone batteries, resulting in an unprecedented amount of information (almost 10,000 photos totaling 50GB) with a resolution of roughly a square inch per pixel.

A view from the ashes

Crutsinger found that post-processing was the biggest challenge due to the sheer quantity of data and the quick turnaround times needed by the authorities and media channels. Transferring large volumes of data from SD cards to external hard drives and then to computers, uploading and downloading data from cloud platforms all added time to processing and delivering final products.

He recalls, “I’d never worked with such massive datasets before—but I knew people who had. I called the Pix4D technical assistance in the San Francisco office.”

With help from Pix4D, all images were processed into a single Pix4Dmapper file in just under 46 hours, producing a 3D densified point cloud, a 3D textured mesh and a high-resolution 1GB orthomosaic map.

Crutsinger adds, “The power of Pix4Dmapper is its ability to quickly process imagery into a super high-resolution map for better decision-making.”

Easy visualization

To make the map data more manageable for Madigan and his team to use in the field, Crutsinger worked with Mapbox, an open source map visualization platform.

He adds, “Within 24 hours, Mapbox created a viewable online map with streets and even the individual addresses of each home, or where each home had been. They were also able to overlay the panoramic images from the neighborhoods in which they had been taken.”

In summary, by connecting the maps, public agencies and, not long after, residents were able to see each burn in detail and context of the neighborhood, even before they were allowed back in the neighborhood.

Madigan adds, “Beyond the public safety, the data was also useful for cross-agency coordination and post-scene documentation. For instance, the data was collected for the Sonoma County emergency managers to better assist with situational awareness and to see firsthand the vast amount of damages to the neighborhoods.”

The maps have been available to the public since the fires and continue to be viewed. As well as providing valuable insights to public safety officials, they live on in articles on The New York Times, Motherboard, and Mapbox.