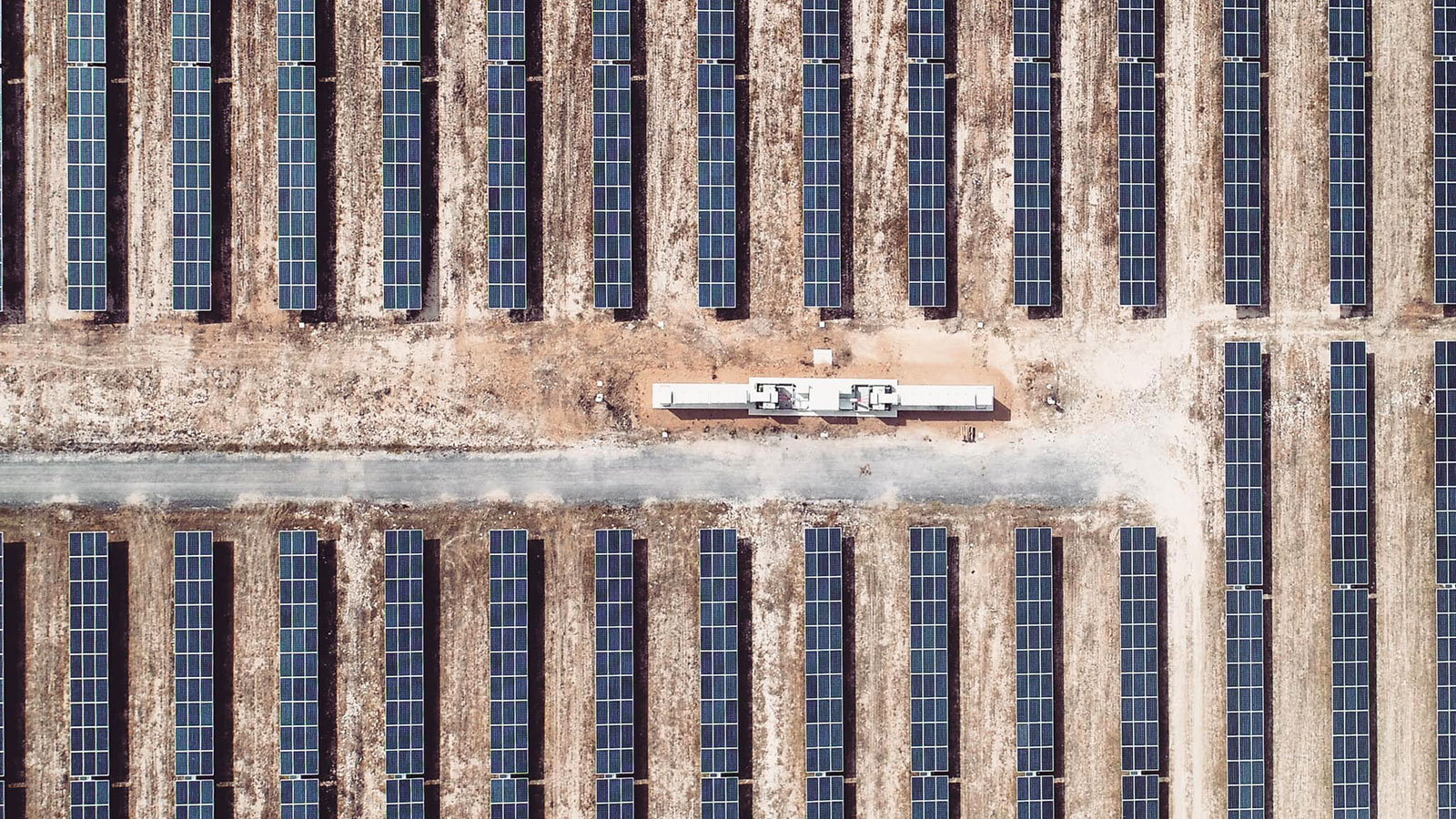

Site surveying for a controlled implosion

Everything has a lifespan.

The Brayton Point Power Plant was once the largest coal-fired generating station in New England, USA. From 1963 to 2017, it pumped out power (and emissions) to the state of Massachusetts. 1.5 million homes were powered by the some 13,000 tons of coal the plant burned every day.

The power plant’s cooling towers were a late addition to the site. Although they were in use for less than a decade before the plant closed, they were an imposing feature visible, across the bay.

In 2019, the final two 500-foot cooling towers were slated for demolition by controlled implosion. But before that work could begin, the demo team needed an up to date site plan.

Project details: Brayton Point cooling towers

| Location | Somerset Massachusetts, USA |

| Survey team | CivilView |

| Area | 350 acres |

| Drones | Custom-built fixed wing drone DJI Phantom 4 Pro |

| Camera | Sony QX-1 with 35mm lens |

| GPS | Leica RTK GS14 |

| Software | Pix4Dmapper Autodesk Civil3D |

| Processing time | ~48 hours |

| Outputs | Site plan Orthomosaic |

| GSD | 2cm |

First, build your drone

“The project took a couple of months,” says Jim Hanley, President of CivilView. “First, we had to build a fixed-wing.”

Hanley explains that while most drone pilots buy one off the shelf, he preferred to build his own. Using a styrofoam shell as a base, Hanley and his team built the drone with Pixhawk hardware.

Hanley explains, “I think that if you use a typical drone, you get typical results. And I want to figure out how to get better results.”

“We have the technological capabilities with the team that we have, and in the end it was a cheaper solution for us to get the results we wanted,” adds Andy Street, Vice President of CivilView Inc.

“It’s easy to build a really crappy drone. I’ve built many of them!” jokes Hanley. “But the good ones take a lot more fine-tuning.”

Once the drone was completed and tested, the CivilView team hit the road and headed to the Brayton Point Power Plant.

Mapping Brayton Point: 20x faster than a traditional survey

Street comments: “With the amount of stuff on the ground, it would have taken forever to run around that site with the old crews. To generate all that information with conventional information would have taken our survey crews at least a month. If not more.”

Hanley and Street estimate the drone mapping survey was completed 20 times faster than a traditional surveying project. Capturing the data took the team a full day, and in under a week, they were able to deliver the completed outputs.

While the project was faster, easier and more cost-effective than a traditional survey, it wasn’t without its challenges.

Winds swept across the bay, rocking the drone - “We were flying on a point, an isthmus, really out into the water body,” says Hanley. In high winds, fixed wing drones typically perform better than rotary drones - something the team discovered as a DJI Phantom 4 Pro was flown in parallel, capturing the front of the cooling towers.

The drones weren’t the only things in the air.

“We had predatory birds, ospreys, flying around,” says Hanley The team were careful to avoid the endangered hawks, which are protected throughout the US. “These ospreys - I don’t want to say they were aggressive but they were inquisitive!”

From drone images to site survey

The handmade drone wasn’t the only new piece of kit in this project. “We bought new hardware just for this project,” says Hanley.

“We had 3,500 high res images, if I had to upload that project on my computer it might take half an hour. But once we had our new hardware, nothing went wrong.” Hanley continues: “We get the project loaded up, get it georeferenced, and let it run through the initial stage overnight. In the morning, we see how it looks, and if the project looks good, we just let her rip. As the owner of a business, I love the idea that I can have something going 24/7 maybe making a little bit of money!”CivilView has been working with drones for surveying for around five years. “As a small company, we were able to provide a cutting edge service that even big companies in our area weren’t providing at the time, although they’re now moving into it and doing really well. We try to leverage the efficiency of drones and Pix4D photogrammetry software to do our surveys a little bit faster, beat some timelines and try and make a little bit of money at the end of the day.”

Hanley adds: “It’s been super fun. It’s been an opportunity to learn something new in a very very old industry using new technology.”

Demolition through controlled implosion

Taking down a structure without damaging its immediate surroundings can take almost as much time as putting it up. That’s why many landowners turn towards controlled implosion. By placing small amounts of explosives in strategic locations on the structure, a controlled demolition expert can weaken the structure sufficiently that it simply collapses.

To help the controlled demolition experts plan the blast, the CivilView team provided a CAD file. “We converted the point cloud with the help of the ortho into a 2D plan. It had all the features of the site, all the topography, labeled up so it looked like a typical existing conditions plan that we would provide if we did a conventional survey,” explains Hanley.

Less typically, the team were also able to provide the 3D textured mesh and orthomosaic. “It’s always interesting and eye catching,” says Hanley. “The ortho has huge value for something like this.”

The controlled implosion set a world record for the tallest cooling tower implosion. The two 500-foot towers were felled in just six seconds.

The demolition completed successfully, the site could be cleared - and the data was still useful. Specific elevations pulled from the site survey were provided to FEMA, for example. “The survey will come into play if they’re looking for long term options to redevelop. It’s the gift that keeps on giving,” Hanley jokes.

The redevelopment plans are still being finalised, but it seems sure to include a wind farm.

Hanley continues on a more serious note: “I also thought this was interesting that this was going from the last coal fired power plant in the state to a staging area for offshore wind.”

“We go from this carbon monster, old world technology to at least a portion of the site as a staging area for offshore wind - it’s cool to be part of something like that.”