How big is too big to map with drones?

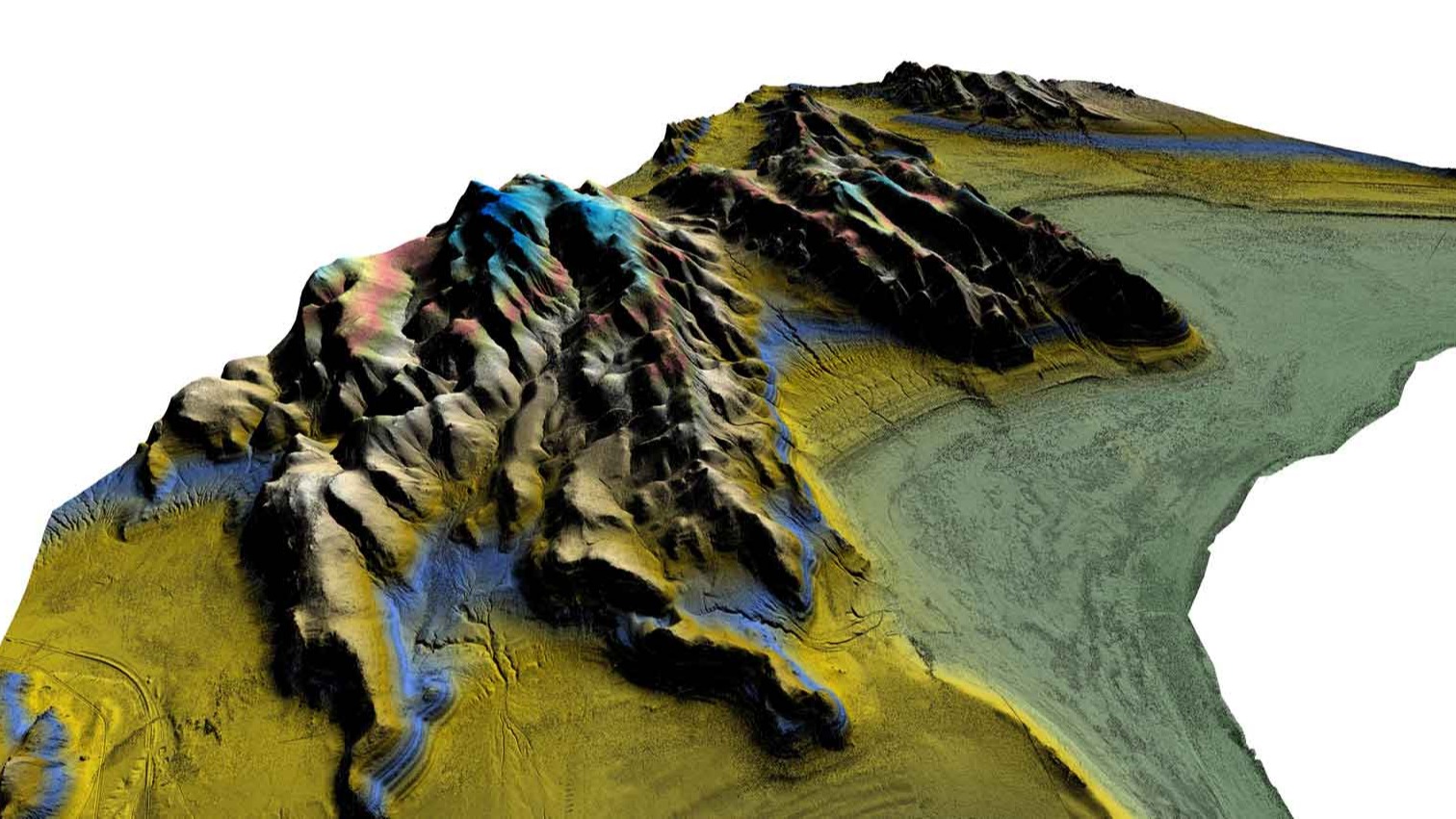

Somewhere in 260 square kilometers of the mountainous Western United States, an energy company suspected that there was the perfect place for a new geothermal power plant.

The area was well-known for its thermal geyser - locals had even carved a hot tub into the banks of the thermal river which flowed into the lake.

But while they suspected it would be the perfect place for a geothermal plant, the company needed to prove it before breaking ground.

That’s where MWH Geo-Surveys came in. Equipped with VTOL (vertical take off and landing) and fixed wing drones, the team flew more than 300 flights to map 262 square kilometers with both thermal and RGB cameras.

Watch the on-demand webinar recording

Watch this story as a webinar. Marshall MacNabb, Senior Data Consultant from MWH Geo-Surveys discusses the project, including the project workflow and actionable tips.

Pushing the limits: mapping large areas with drones

MWH Geo-Surveys mapped more than 260 square kilometers of the mountainous Western United States. It’s one of the biggest surveys we’ve seen: but potentially not the largest. How big is too big to map with drones?

As discussed in the webinar, there are many different applications and industries where large scale mapping is essential. These include:

- Oil and gas: such as seismic mapping support and infrastructure planning

- Mining: including large scale inventory tracking and rapid assessment of stockpiles

- Environmental: wetland easement monitoring and wildlife protection call for mapping large areas

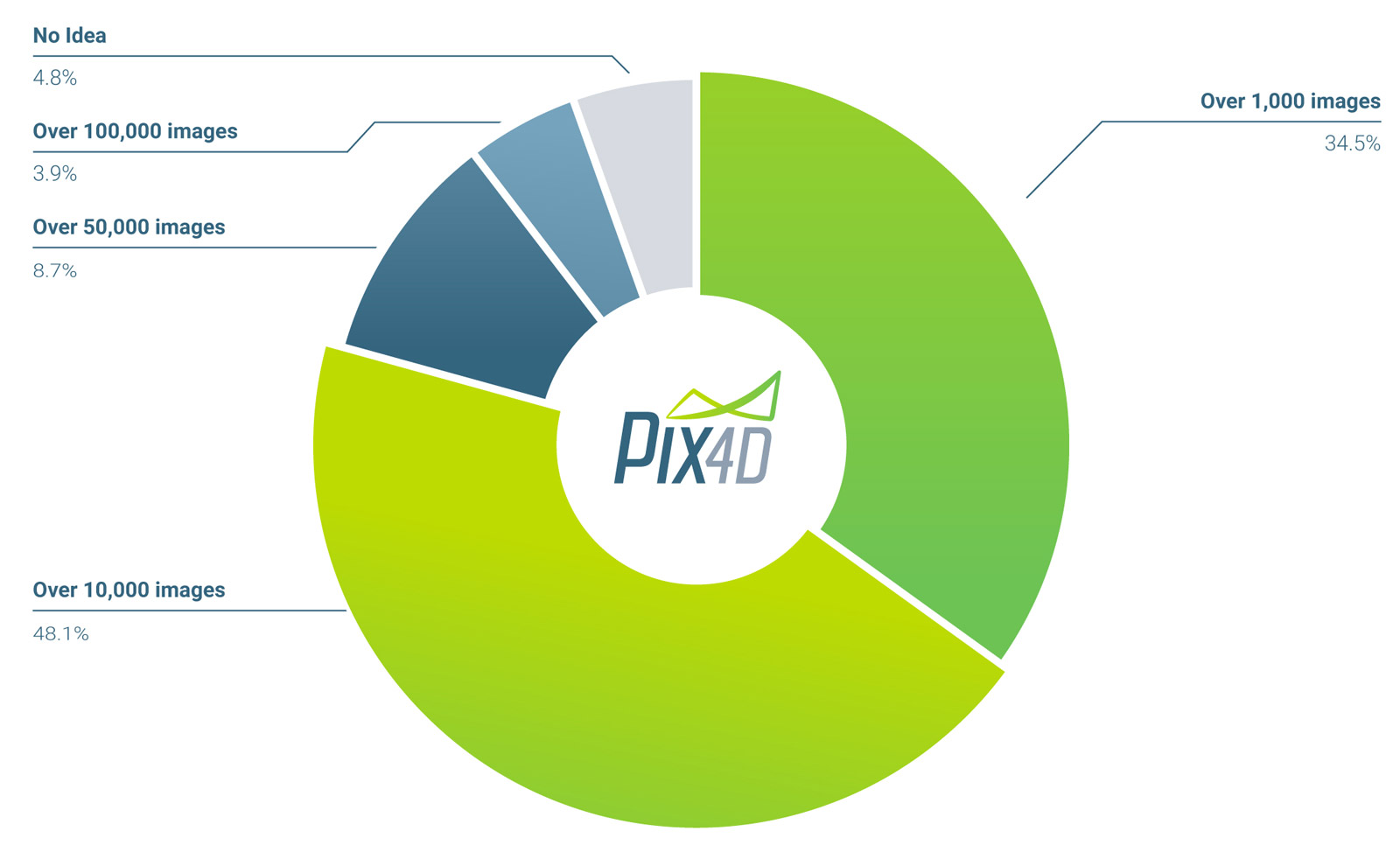

But what does ‘large project’ mean? 48% of webinar attendees of our webinar defined a ‘large’ project as containing over 10,000 images.

How big is a big project?

MacNabb defines ‘large’ as a project which can’t be processed in a single Pix4Dmapper project, but requires merging into a ‘mega-project’.

This blog post will discuss one such mega-project. Watch the webinar for more discussions of large projects around the world.

Project details

| Company | MWH Geo-Surveys |

| Location | Western United States |

| Drones | Wingtra One (Sony RX1R II) senseFly eBee (S.O.D.A and thermoMAP) |

| Software | Pix4Dmapper Custom photo management tool |

| Processing hardware | Custom built desktop computers |

| Area surveyed | 262 square kilometers (101 square miles) |

| Total images | 141,544 geotagged images |

| GCPs | 328 |

| Project size | 1.74 TB |

| GSD | 5 cm |

Aerial mapping a large area with drones

Mapping more than 260 square kilometers took the MWH Geo-Survey team around 6 weeks.

The same area could have been covered more quickly with a light aircraft, but it would have been logistically prohibitive to refly areas.

In order to fly all day, the drone crew brought a generator and solar panels to recharge the drones batteries. They also packed a lot of SD cards: without having the pause and download the data they could swap out a card and relaunch the drone. At the end of the day, all the data would be downloaded and organised.

Big data, big challenges

“Usually you would just start the import straight into Pix4Dmapper,’ says MacNabb. ‘But our workflow deviates a little here as I created a custom program to manage all the photos and see what has and hasn’t been flown.”

Before the project was complete, MacNabb captured more than 141,000 photos. Any dataset of that size needed special handling, or vital information could be lost in the shuffle - or duplicated, causing strain on already hard-working servers.

“One of the biggest problems which has been interesting to tackle has just been managing the data. There are just so many photos and so many terabytes of data that when you have the raw data plus the processed data you just end up needing terabytes and terabytes of storage.”

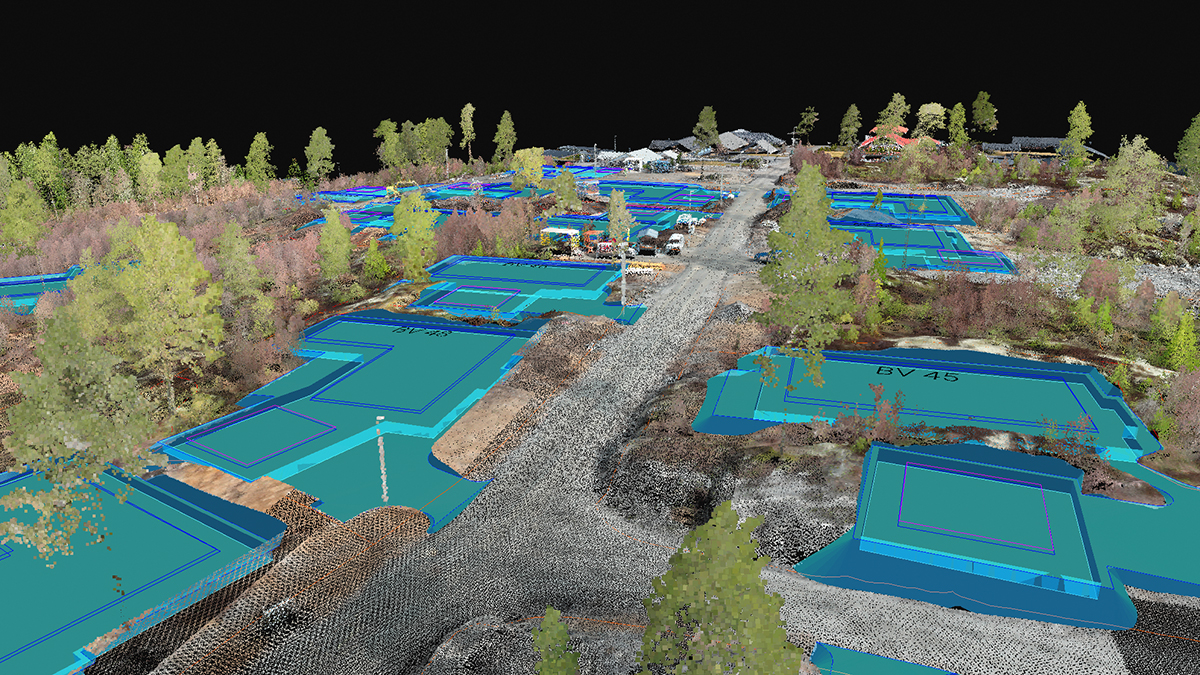

MacNabb’s custom program grouped data from multiple flights in ‘zones’, and the files within conformed to a strict naming convention, based on the date, time and zone. Each zone contained approximately 8,000 photos and was processed separately and then stitched together.He explains: “If you conduct a Pix4D project and you survey it well with adequate ground control and it’s done with rigorous quality standards, it means you can trust the DSM that you’re generating to not have errors, it means that there’s no limitation in combining two Pix4D projects with a seamless boundary between them... You can continue to combine these tiles into larger and larger areas.”

The right tool for the job

“If we were working locally, we would have considered Pix4Dengine for this job,” says MacNabb. “That would allow us to upload the data to AWS right away and do the processing like that. Instead, we’ve got a bit of a unique situation: our data is collected in remote areas of the world which do not have great internet - for some of these projects we were mailing hard drives across the world, because that was faster than trying to upload from the Arctic circle! It made more sense for us to handle the entire data process within-office and to be able to plug in a hard drive that has a month worth of survey data collected on it and transfer that to our computer in-house.”

While some files can be processed in the field, most of it was handled in the office on two custom-built PCs.

“You could call them gaming PCs, but that would be underselling them a bit. Basically the computers are using as many top-of-the-line off-the-shelf components that you can buy.” The water-cooled computers are maxxed out with 64 - 128 GB of RAM. An AMD Threadripper CPU handles the processing, M.2 SSDs run the operating system, while the pictures were stored in 8TB HDDs.

“Memory is key,” says MacNabb. “When running these big projects we’ll use up to 80% of the 128 gigs and if you’re trying to process these large blocks with a smaller amount of RAM, you just run out of RAM and it becomes your limiting factor.” MacNabb adds, “Since I built these computers, they’ve had zero days of downtime. They’ve been continuously processing data in Pix4Dmapper for eight months and twelve months straight, respectively.”

While collecting and managing the images took some time, processing them was relatively straightforward. MacNabb and the team found they could use standard settings and get a great result.“If you zoom in you can see the individual sagebrush plants,” says MacNabb. “We can send this dataset to an expert somewhere who doesn’t have to go out into the mountains to look for where the fault is and to be able to get not only a birds-eye view of the area but being able to get right down to little details.

The next steps

The isolation that make the mountains and deserts of the Western United States beautiful also makes it a difficult place to work.

“Doing geology from a desk, potentially hundreds of miles away is a real advantage of using drones and Pix4Dmapper,” says MacNabb. “Instead of sending an expert out into the cold to look for a faultline, we can deliver not only a birds-eye-view but the smallest details right to their desks.”

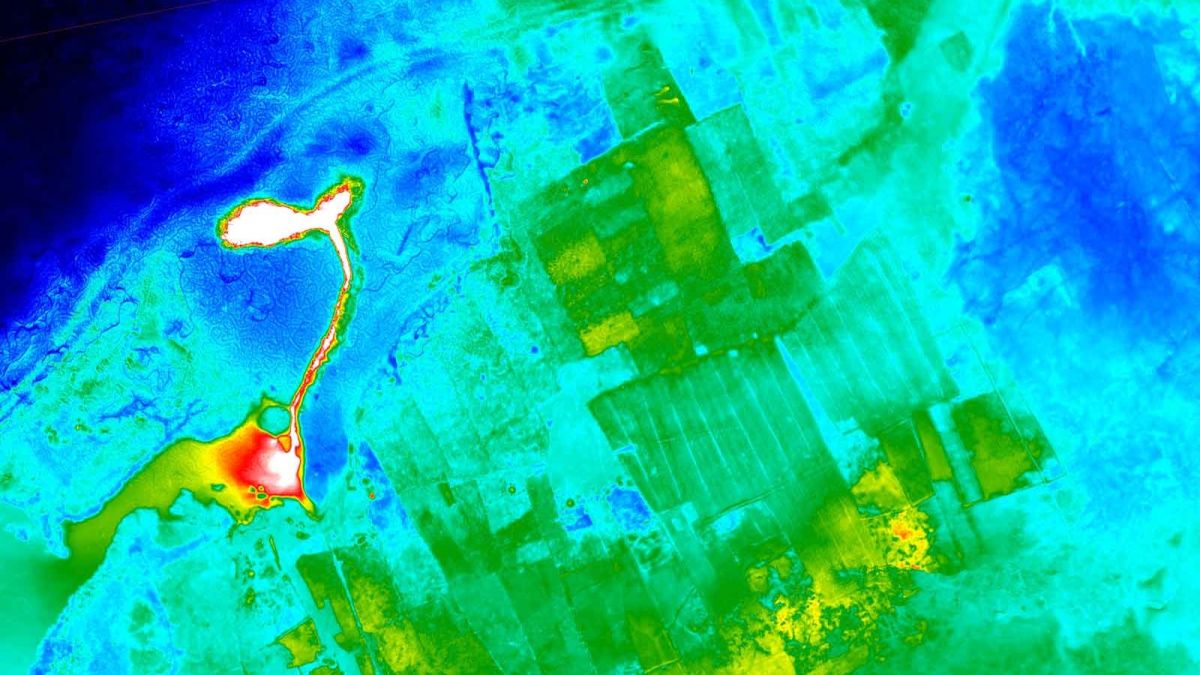

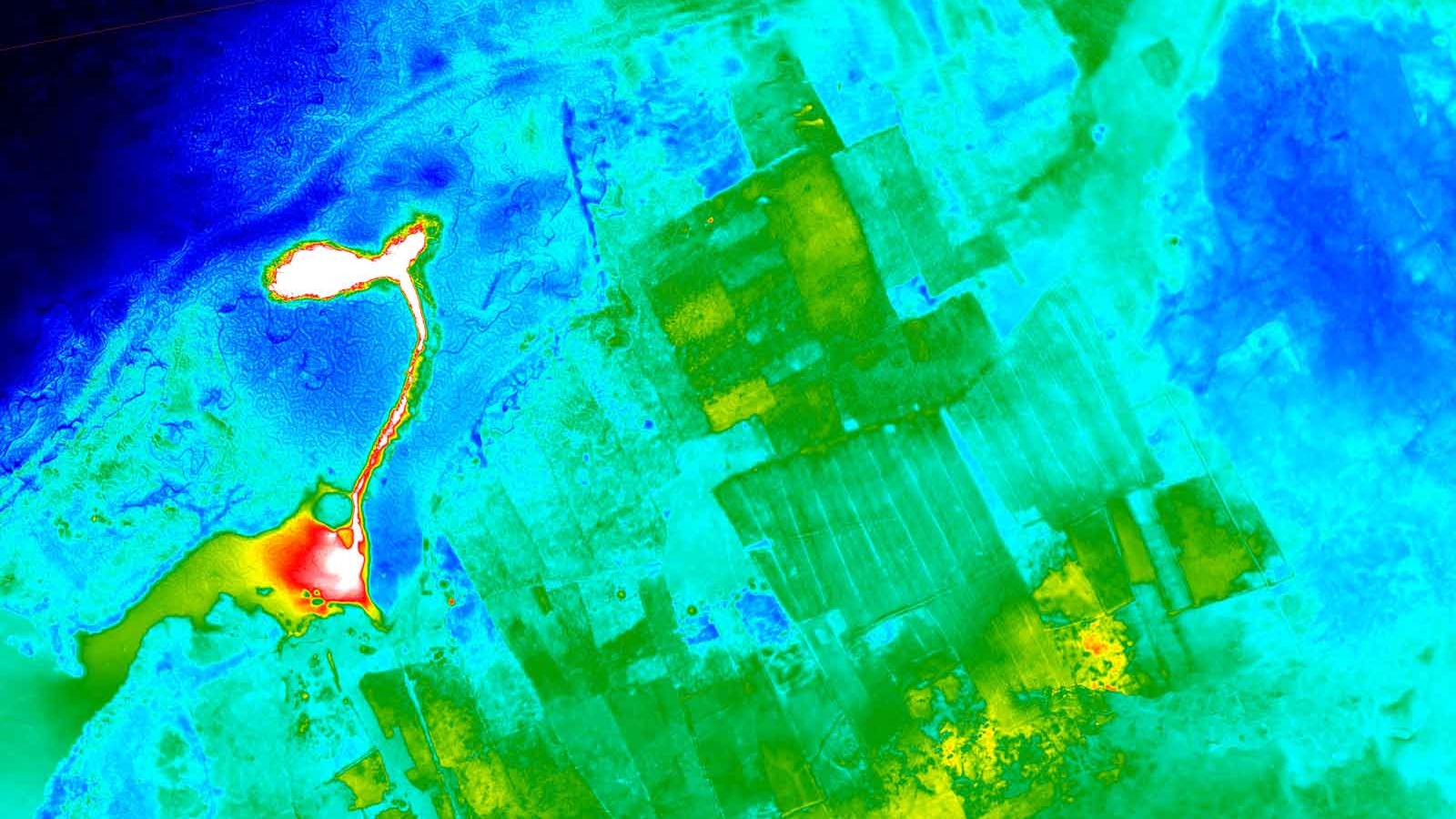

The next steps for MacNabb and the team is building from the RGB images, and taking a thermal study of the area. The closely-flown thermal map looked for hotspots close to the surface.

Remarkable results with standard settings

Average drone mapping projects use less than a thousand photos. This project used a hundred times that.

Yet MacNabb notes that the data was collected with off-the-shelf drones and processed in Pix4Dmapper “using fairly standard settings.”

While MWH Geo-Surveys’ 35-year history in GIS meant the team had a wealth of knowledge to draw upon, he feels that the custom data management program isn’t essential.

“I would say there’s no reason that this entire thing can’t be done with a standard Pix4Dmapper software and a standard drone.”