Estimating rockfall danger after a landslide

In October, 2015, a landslide occurred in a mountainous area of Switzerland, close to the Italian border. One side of a mountain cliff, tracing back to the 17th century, had been seriously damaged and deplaced due to particular underground water floods, making it more prone to collapse than the other side.

Because of this frequent collapse and the resulting landslides, a forest road was built to stop the collapse through monitoring, inspection, and renaturation. However, after the big 2015 landslide, a large falling rock stopped by a bottleneck in the cliff, over the forest road.

In order to send workers in to clean up the road, located directly beneath the rock, an immediate decision needed to be made by the local geological department on whether it would be safe to leave the rock or it would be necessary to blast it.

Pix4Dmapper software enabled the volume estimation of falling rock and height of the fall to assist the government in making this vital decision.

Mapping the danger zone

The canton of Ticino’s geological department contacted Oblivion Aerial for high resolution (close-up) images of the falling rock. Damiano Maeder, in charge of the project, used a DJI Phantom 4 to acquire images of both the rock and the surrounded cliff, flying manually with the camera shutter triggered every two seconds.

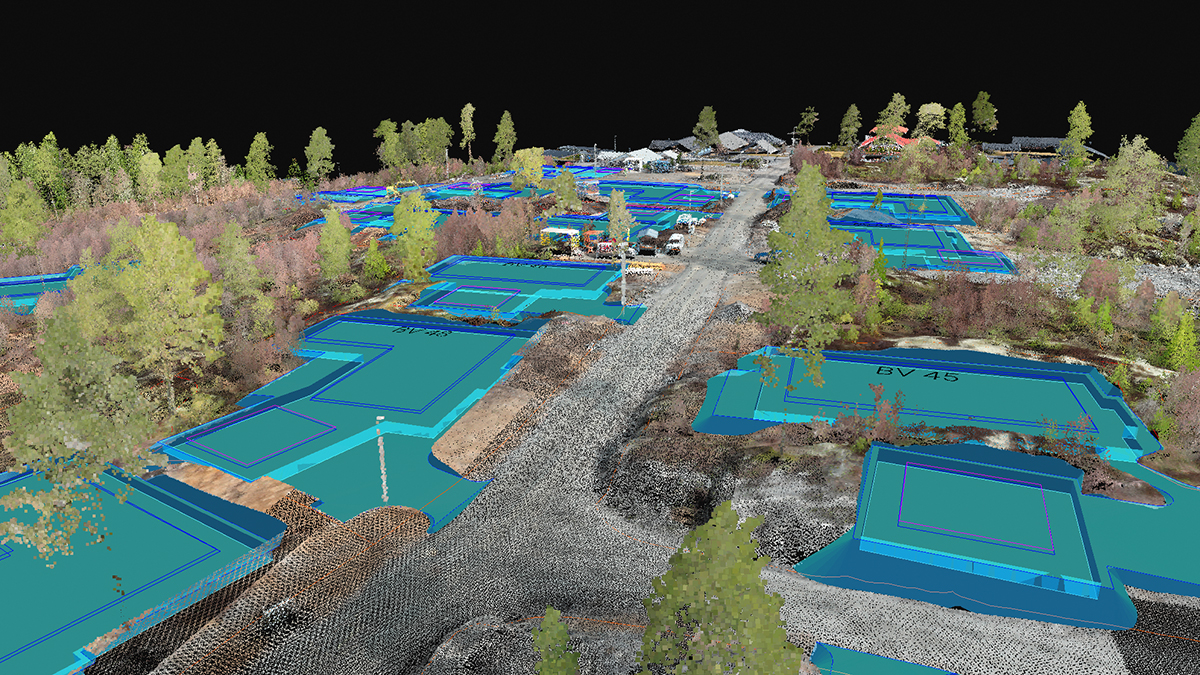

After automatically processing in Pix4Dmapper, the team was able to create a full 3D reconstruction of the entire cliff. All image geocoordinates are recorded in the EXIF file by the camera-embedded GPS. With these image geotags, results can be measured directly in the software. The outcome went far beyond the original requirement and played an important role in the final decision making.

The volume of the rock was measured as around 150 cubic meters, and weight was estimated to be around 375 tonnes, by applying a conversion according to the material composing the rock. In this case, the main component was granite, with a density of 2.5 kg/dm^3, and the weight is calculated as 2.5 x 150’000 = 375’000 kg (375 tonnes).

An alternative way to make these estimations, brought up for discussion during the case, was to use two laser scanners pointed at the rock. However, this would eventually cost around 3,000 CHF per day after evaluation and makes for an unaffordable solution.

Image analyis and decision making

After analyzing the landscape, the evaluation was also done based on the geologist’s experience. The geology department decided to keep the rock where it is for now, because according to the size, volume, and height of the rock, even if it continues falling, the smaller rocks underneath will be pushed to the bottleneck and the weight of the big rock will force all to block each other and eventually stop.

The conclusion was made that there is no immediate danger of the rock falling, but the team decided to go back six months later to monitor the same target and recheck status: using the same drone mapping techniques and Pix4D software!