DRONEBIRD disaster rescue squad

“Japan is a disaster powerhouse,” says Taichi Furuhashi of Crisis Mappers Japan. The island nation has over a hundred volcanoes, is prone to earthquakes, and its long coastline is exposed to tsunamis.

In October 2019, the category 5 super-typhoon Hagibis hit Japan. More than 200,000 people evacuated, but despite this exodus, at least 30 people were killed, and a further 15 remain missing. On the same day that Hagibis reached Japan, a magnitude 5.7 earthquake occurred off the coastline, worsening the already dangerous conditions.

Within 24 hours, DRONEBIRDs were mapping the affected areas.

Meet the DRONEBIRDs

“If a major natural disaster occurs, the first thing you need is an accurate map that gives you a clear picture of the situation,” says Professor Taichi Furuhashi, “But what would happen if there was no map during a disaster? If an eruption occurred, how far has the lava spread?If a major earthquake occurs, which roads are safe and which are dangerous? If a flood or large-scale fire occurs, where would you escape?”

The effort is inspired in part by the miracle of Kamaishi, the fast and safe evacuation of 3,000 students after the 2011 tsunami which claimed so many lives.

“If there is even one DRONEBIRD in a group, they can share information about the extent of the danger. If we can train in advance, we will improve the ability of each citizen to help themselves and their community in a disaster,” says Professor Furuhashi.

“'The moment a road is no longer a road' is when the DRONEBIRDs start to fly.”

Ready for anything: planning for disaster

When a natural disaster occurs, DRONEBIRD maps it. Information is released on OpenStreetMap to support life-saving relief efforts.

The traditional response to mapping a disaster has been satellite imagery and ‘windshield assessments’ on the ground. Both options are costly and take time to deploy.

As of February 2020, there are 582 DRONEBIRD members, who have created crisis maps 32 times.

One of their most recent efforts was in the aftermath of super-typhoon Hagibis.

Mapping the aftermath of Typhoon Hagibis

The DRONEBIRD volunteers have a tough job. The drone pilots leave their families in the immediate aftermath of a disaster to support the wider community, in what are by definition difficult conditions.

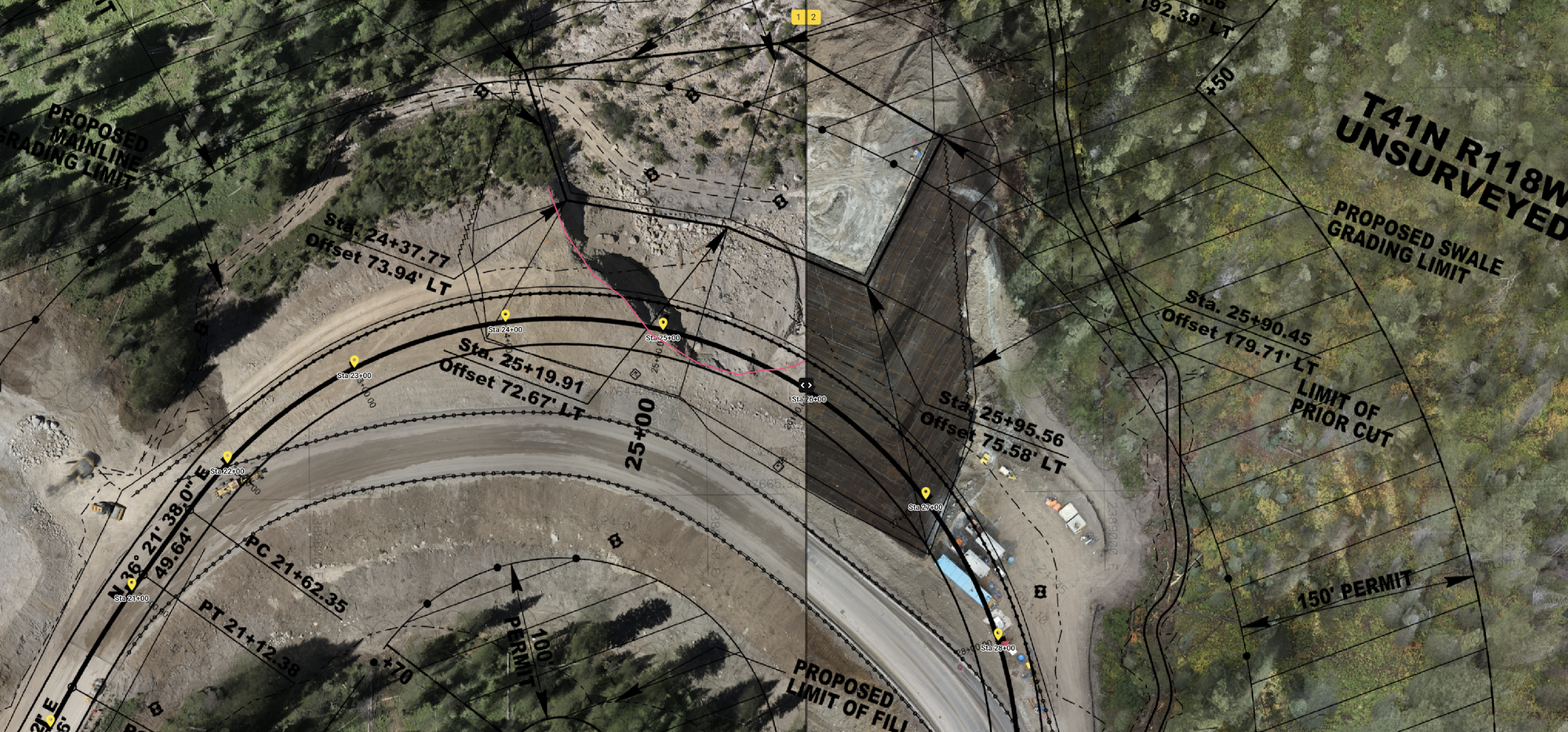

After Typhoon Hagibis hit, DRONEBIRDs mobilized, capturing data in affected areas including Sagamihara, Chofu/Komae, Setagaya, Machida and Kimitsu to understand the extent of the damage.

Project details: Documenting a disaster

| Team | DRONEBIRD |

| Hardware |

|

| Software | Pix4Dcloud |

| Maps created | 12 |

| Total images (across all maps) | Approximately 5,000 |

| Total mapped area | Approximately 50km² |

| Time to completion |

|

| Accuracy | GCPs were not used, but some of the drone fleet (eBee X) used RTK |

| Typical GSD | 3-5cm per pixel |

| Outputs | Orthomosaic GeoTIFF, DSM, point cloud |

| Collaborators |

The first challenge: getting to the affected area.

Professor Furuhashi recalls: “Sagamihara City is a mountainous area with very steep terrain, so it was very difficult to move due to a lot of traffic and congestion. On October 14, the weather conditions were bad and the rain stopped. We did fly then, but after that we chose days with good weather conditions as much as possible. We always put the safety of the teams on the ground first.”

Timeline: Super-typhoon Hagibis, October 2019

| October 12 (Saturday) |

|

| October 14 (Monday) |

|

| October 16 (Wednesday) |

|

| October 20 (Sunday) |

|

| October 22 (Tuesday) |

|

| October 27 (Sunday) |

|

Flying a disaster zone

DRONEBIRDs don’t fly alone. Professor Furuhashi comments: “In the confusion following super-typhoon Hagibis, teamwork was essential. As well as piloting the drone, team members need to explain the details of the disaster agreement to residents in the affected areas, request cooperation for takeoff and landing sites and more. Each team must include a drone pilot and at least one assistant, with a minimum of two to three people.”

DRONEBIRD and Crisis Mappers Japan work closely with local governments and air traffic controllers, and 28 local governments that have signed disaster prevention agreements. The teams operate within Article 132 of Japanese Aviation Law, which usually prohibits flying drones over residential areas. But DRONEBIRD has agreements with many local governments, with exceptions in place for exceptional circumstances. “With these plans in place, we can capture images relatively smoothly in the midst of chaos,” says Professor Furuhashi.

Each DRONEBIRD team reached the affected area within 48 hours of the typhoon making landfall.

The first step was finding the best place for take off and landing. The DRONEBIRD team has a variety of drones in their fleet, including the fixed wing eBee X and the popular rotary drone, the DJI Phantom 4 Pro. The smaller rotary drone needs less room to launch, but the team found the senseFly eBee X valuable for large area mapping. Of the approximately 50 km² mapped, more than half of it was captured by the eBee X.

The team did not place ground control points, as the rapidly changing situation made them difficult to handle. However, the eBee X is equipped with RTK technology, and the drone pilots captured 70% overlap, so creating accurate maps in Pix4Dcloud was easy.

Results within 48 hours

Thanks to excellent planning, the right tech and the right team, DRONEBIRD took just 48 hours to capture images, create orthomosaics and release the data.

Because the images were processed on Pix4Dcloud, they were available to be viewed immediately by municipal officials. Thanks to the cloud-based system, some analysis could be completed by office-based teams, while the field teams moving from site to site.

Professor Taichi Furuhashi, director of the non-profit corporation Crisis Mappers Japan, who led this crisis mapping, said, "We used other software together, but as a result we were able to process large volumes of data efficiently. Pix4Dcloud was effective for DRONEBIRD's activities."

Within ten days of the typhoon making landfall, the information was available to the general public. Aligning with DRONEBIRD’s citizen-first open-access policy, orthomosaics were released on OpenAerialMap, and original images and XYZ tile image data are available on Github as downloadable data under a Creative Commons license. DRONEBIRD's workflow is to update OpenStreetMap based on the information released on OpenAerialMap.

The information was used by local governments to plan the cleanup.

Professor Furuhashi explains: "Since this aerial photography support (by DRONEBIRD) was the first case for the local governments involved, I feel that it is still a trial and error process for using the outputs - the orthomosaic maps. Kimitsu City used the maps as auxiliary data for issuing affliction certificate, and Sagamihara City's chief used the maps as basic data for explanation of the damage situation, so different cities used the maps on their own ways. The captured data and the processed maps can be browsed at any time, so I think there will be more usage of these sets of data as training data, to prepare for the next disaster."

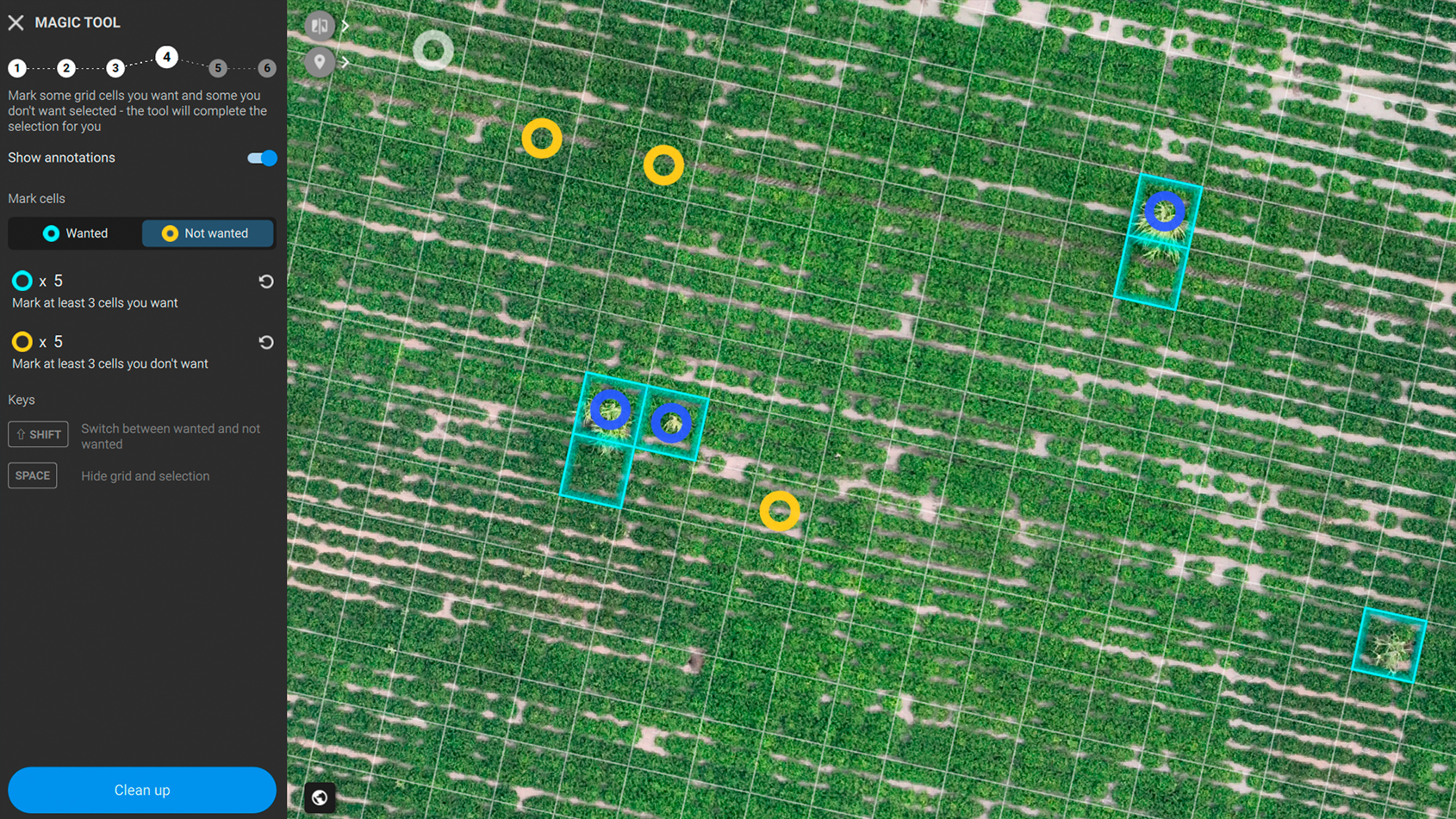

Planning for the next disaster and testing Pix4Dreact

Pix4Dreact was released after super-typhoon Hagibis, but the DRONEBIRD team has been actively working to test the software before the next disaster. Pix4Dreact is 2D fast-mapping software designed for public safety and emergency response.

Unlike Pix4Dcloud, which processes projects online, Pix4Dreact works entirely offline, and can be run on a basic laptop.

Professor Furuhashi comments: “A notebook PC is powerful enough to process a dataset of a hundred photos in Pix4Dreact. It is useful for working in an offline environment."

In a “disaster powerhouse”, preparedness is key. In quieter moments, DRONEBIRDs hone their skills, train more drone pilots, and scale up their operation by gaining experience with different types of drones. The team knows there will be many situations where drone mapping will be used to understand disaster damage. When disaster strikes, the DRONEBIRDs will be ready.

| We would like to thank Professor Taichi Furuhashi, the DRONEBIRD team and everyone involved in preparing this article. |