Cleaning up after the 2019/2020 Australian bushfires

Fire and Rescue New South Wales (FRNSW) is one of the world’s largest urban fire and rescue services and is the busiest in Australia. In the summer of 2019/2020, they faced their biggest challenge yet as devastating wildfires raged across the country.

The fires of Australia’s Black Summer burned 5 million hectares of New South Wales alone. Over 8,000 buildings were destroyed, and the recovery is predicted to cost billions. The FRNSW team of more than 3,500 full time firefighters, 7,800 part time and community volunteer firefighters, plus almost 500 administrative and trade staff, saw the devastation first-hand as they battled the fires.

Once the bushfires were being effectively controlled, the focus of operations shifted to recovery.

The first step of the cleanup is estimating the sheer amount of waste left behind.

What’s left behind

What would you save if your house was on fire? What would you be forced to leave - and what happens next?

“The first step to recovery after a disaster event is dealing with all the debris - physically removing the visible impact so the community healing can begin,” explains Katherine Tuinman-Neal, the Data Systems and GIS specialist from the FRNSW Bushfire and Aviation Unit.

The New South Wales government has committed to covering the cost of the cleanup, and the FRNSW team were deployed to take the first steps.

How firefighters work with UAVs in Australia

Fire and Rescue New South Wales has been working with drone technology since 2015. In 2017 a new UAV team was launched: the FRNSW Bushfire and Aviation Unit. The team consists of Aviation Technical Officers, a Team Leader, a Data and Systems Specialist and a SuperIntendent who manages the unit.

The team has undertaken a wide range of projects. As Tuinman-Neal explains, these include: “Flood response, hazmat incidents, supporting bushfire operations, subterranean fire monitoring, post-incident disaster assistance recovery, fuel fire in a container ship, tanker fires, pre-event risk assessments, prescribed burning, environmental monitoring and of course, volumetric calculation of debris.”

“The purpose of the mission was to estimate the volume of debris using RPAS [Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems], both on an individual property level and the overall quantity in communities and across the state,” Tuinman-Neal continues: “But what amount and type of waste are Waste Authorities dealing with and are the right facilities ready to receive it?”

Everything looks similar when covered with ash, but the FRNSW team knew not every type of waste can be treated in the same way. They sort to classify the types of waste, including:

- Green waste (organic material)

- Recoverable materials

- Vehicles and equipment

- Building waste

- Asbestos waste

- Hazardous waste

Categorizing waste before it’s cleared helps waste management agencies understand the volumes and type of material they will need to deal with and to plan accordingly. Ensuring asbestos or hazardous waste is clearly labeled as such helps those on the ground work safely as they clear areas ‘in the black’.

“The data helps develop a basis for comprehensive local and statewide disposal strategy to ensure that treatment and waste facilities at every level and every step of the way can handle the amounts and types of debris involved as communities start to clean up - while still being able to recycle, reuse or repurpose where possible,” says Tuinman-Neal. “We hope that in knowing more about the types of debris encountered, that the environment will benefit from more recycling and less going to landfill.”

Studying the present to plan for the future

Black Summer was not Australia’s first fire season. And as the climate crisis accelerates extreme weather patterns, it will not be their last. The FRNSW team’s mission was two-fold. First and foremost, to support communities in need. Secondly, to “Determine exactly what post-impact debris existed in the hardest hit communities on the South Coast of New South Wales,” explains Tuinman-Neal. The information gathered will allow the FRNSW Bushfire and Aviation Unit to develop a robust, scalable workflow which can be used in the future.

“We targeted four communities that possessed a differing ‘debris profile’ in order to gain an insight into what the practical side of clean-up recovery would be like,” says Tuinman-Neal. New South Wales’ primary environmental regulator, EPA NSW, worked with FRNSW to determine the best areas to carry out this analysis.

The different ‘community debris profiles’ were broadly classified as:

- Suburbia - Free-standing single-family homes with limited vegetation

- Coastal holiday estate - Widely spaced free-standing homes surrounded by vegetation. The coastal location results in different weather patterns than inland areas

- Semi-rural - Free-standing homes and outbuildings widely dispersed with vegetation

- Rural/remote - Free-standing homes and outbuildings, with extra complications of farm materials and fuel storage

Regardless of the area, the mapping workflow remained the same.

Project details: Estimating waste volume after a disaster

| Location | New South Wales, Australia |

| Team | Fire and Rescue New South Wales Bushfire and Aviation Unit |

| Hardware | DJI M210 with X5S sensor DJI Mavic 2 |

| Software | Pix4Dcapture - drone flight planning software Pix4Dmapper - photogrammetry software |

| Data capture | 5 days total |

| Processing time | 9 hours |

| Data format | RGB .jpg images |

| Total data captured | ~7,500 images 150GB |

| GSD | 2 to 3 cm/px |

| Outputs | Orthomosaics 3D models |

First, the team headed to the affected study areas. Given the scale of New South Wales, traveling between the suburban, coastal, semi-rural and remote areas was a project in itself.

“Data capture took five days over two separate missions,” says Tuinman-Neal. “There were still active fire fighting operations and some of the areas were geographically challenging in terms of distance and required a 4WD SUV to get to. A couple of sites required crossing creeks - mostly by 4WD SUV, although one site required the team to carry all the RPAS gear on foot across a creek to get to a suitable nearby launch site. In total, the team traveled over 1,500 kilometres to cover the community debris profiles and fulfil the data capture requirements.”

Once they arrived on site, the team plotted missions in Pix4Dcapture. “The Team like that Pix4Dcapture is very intuitive to use,” says Tuinman-Neal.

Chief Remote Pilot Anthony Wallgate and Pilot in charge and Chief Maintenance Officer Onur Ayyildiz trained a new RPAS pilot at the same time as doing this project. Training typically starts in a classroom environment, not in the field, but the app is so intuative there were no issues on-boarding the new team member. “They were walked through the Pix4Dcapture app and in a short time were able to operate it themselves.” However, the FRNSW team did find that basemaps needed to be preloaded in Pix4Dcapture, as remote areas had limited internet access.

The FRNSW Bushfire and Aviation Unit’s drone fleet consisted of a DJI M210 equipped with a high resolution X5S sensor. This drone was used for mapping, and a second DJI Mavic 2 was used for site orientations and to capture nadir images for reports. Some of the sites were studded with the distinctive Australian gum tree. Although the trees were burned and stripped of foliage, at 40 metres tall they still posed challenges from a safety and flight planning perspective. However the small fleet of rotary drones coped well with dodging trees, and the winds which picked up every afternoon.

“Other challenges were that the project required UAVs to be used in the vicinity of aircraft operations,” says Tuinman-Neal. “This is not the first time FRNSW has done this and have found that critical to this is a good communications plan between Chief Remote Pilot Anthony Wallgate, Pilot in charge and Chief Maintenance Officer Onur Ayyildiz and Air Operations Manager, with clear parameters around flight areas, heights and duration of flights. Additionally constant monitoring of airband and local manned aircraft frequencies, support crew observations and ongoing communications with pilots are imperative activities to undertake throughout the project timeframe.”

Around 2,300 images were captured in both the suburban and coastal holiday estate areas. The semi-rural and remote areas required closer to 1,400 images.

Once back on the ground, the team ran an initial processing onsite. As well as checking the quality of the output, they reviewed Pix4Dmapper’s Quality Report to ensure enough images were captured and to identify any issues.

“We chose Pix4Dmapper instead of Pix4Dreact because we needed Pix4Dmapper’s 3D for the volumetric calculations,” says Tuinman-Neal. “We can certainly see lots of potential for Fire and Rescue using Pix4Dreact and have a training program being developed and a plan in place to roll it out to our 50 Pilots - it’s currently in testing with our Bushfire Officers.”

Over the five-day mission, the team faced the personal challenge of seeing the extent and personal impact of the fires, both on a local and state-wide level. “Many residents had stories of what occurred as they stayed to defend their homes and many were in the midst of trying to process and cope with losing their homes. This only made the Team more determined to deliver the best data possible to help this community recover,” says Tuinman-Neal.

Consistent results for coordinated action

Detailed processing back in the office took nine hours, and was completed on a “High-specced Dell workstation.”

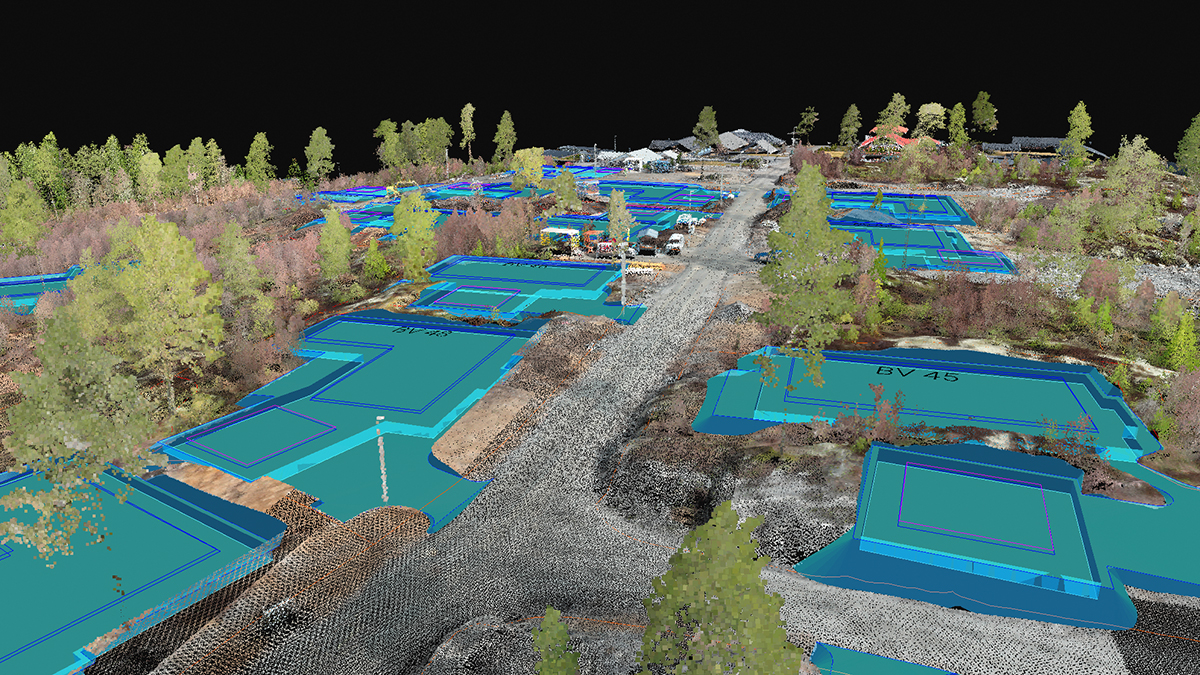

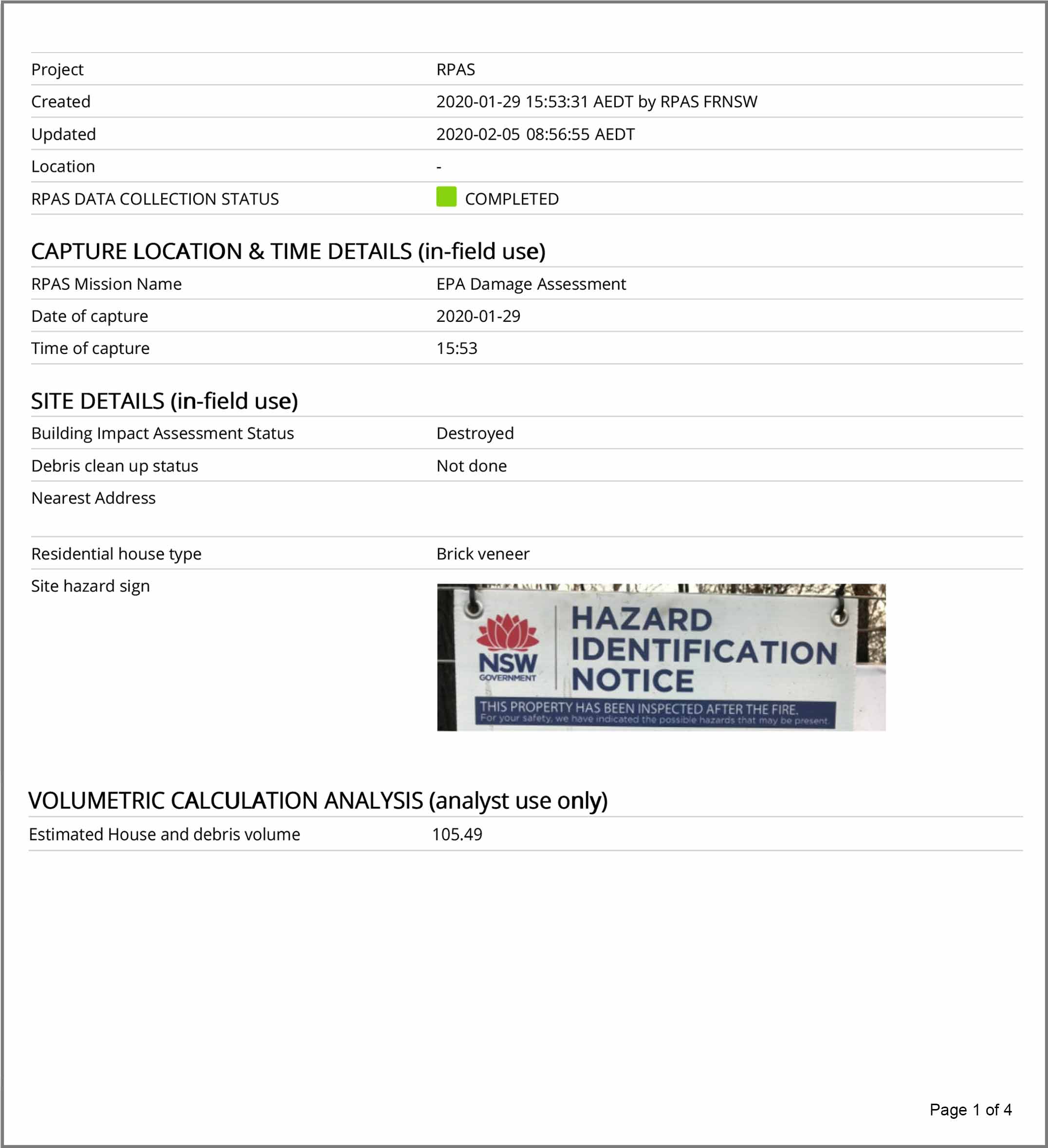

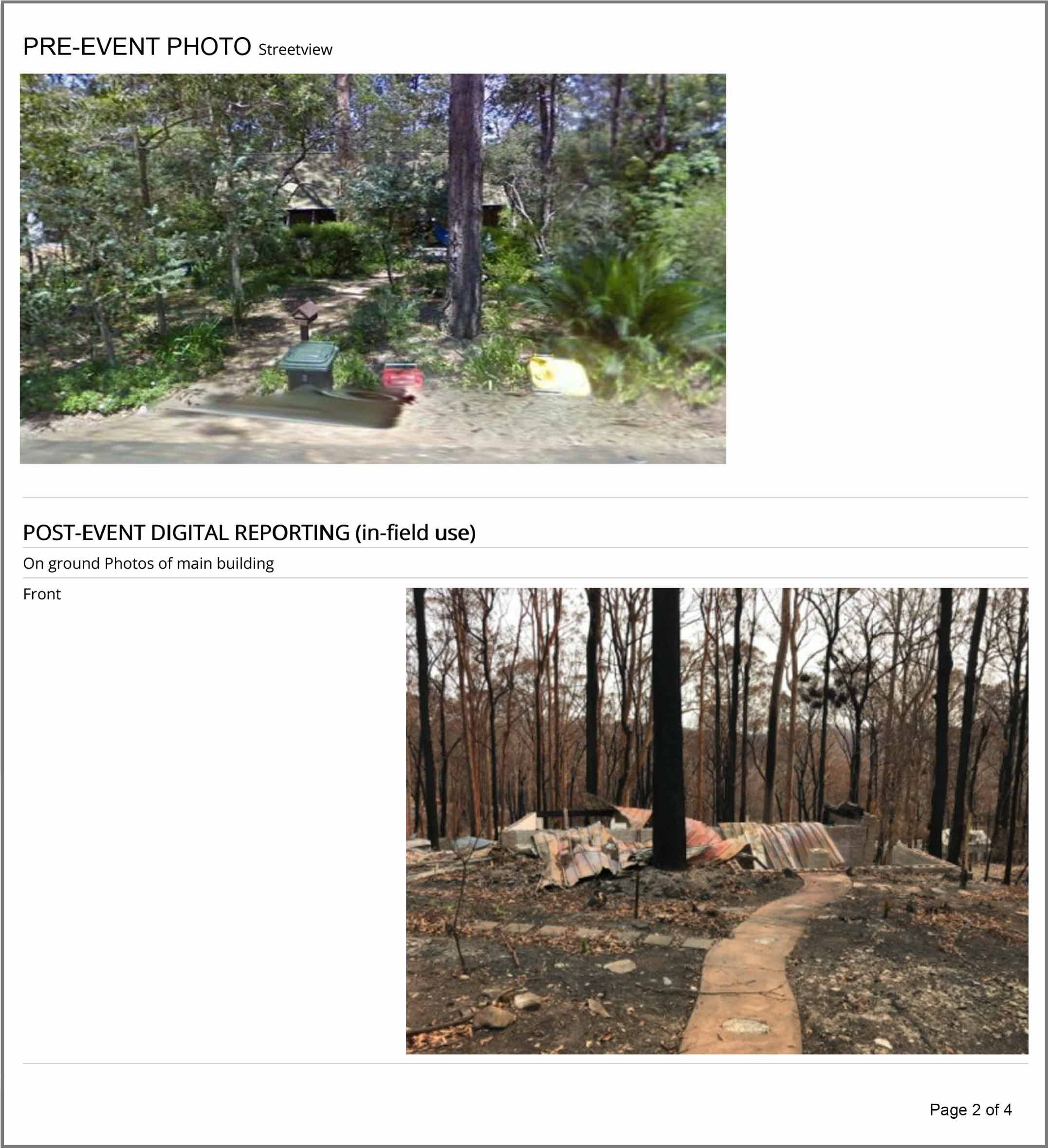

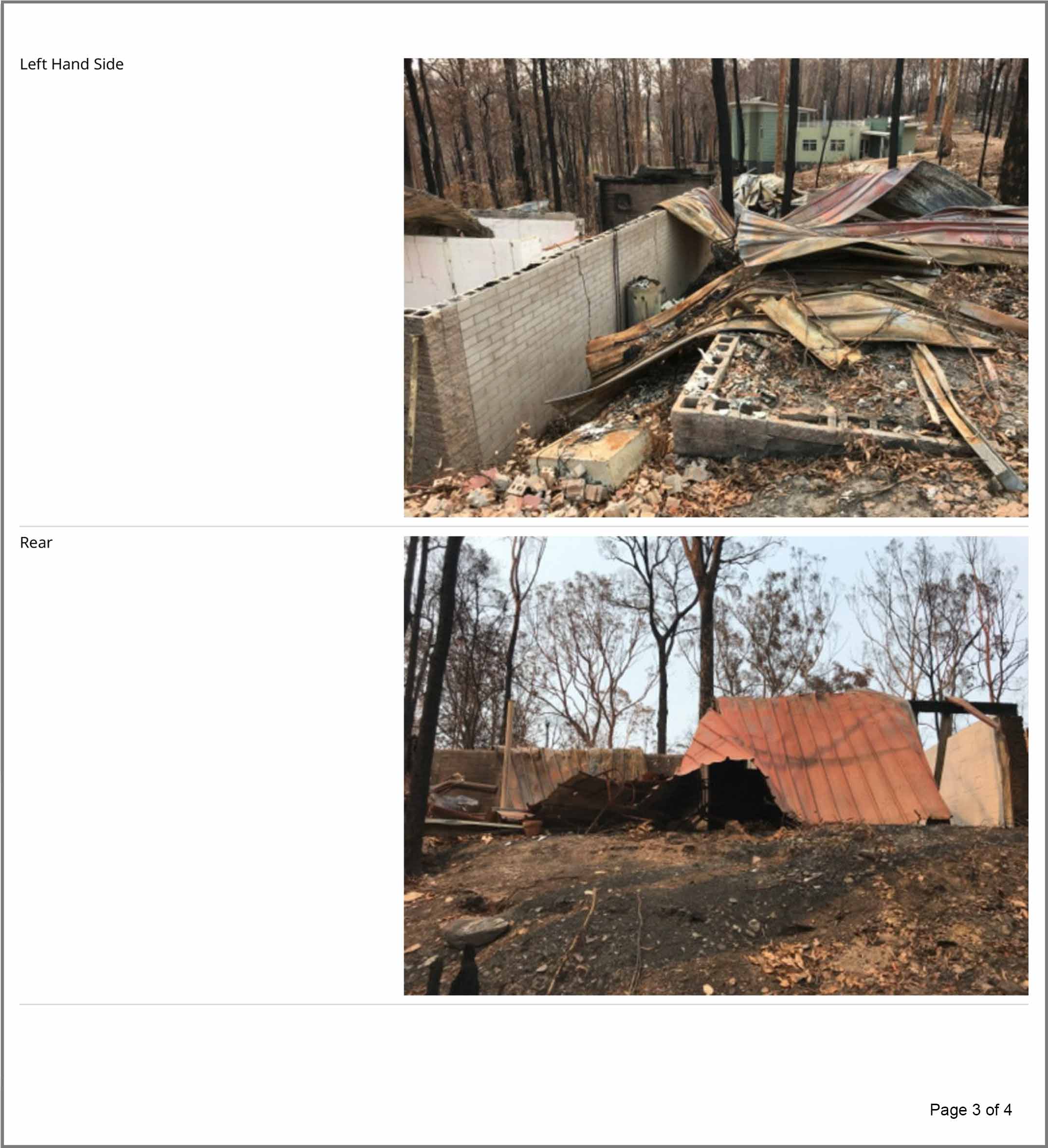

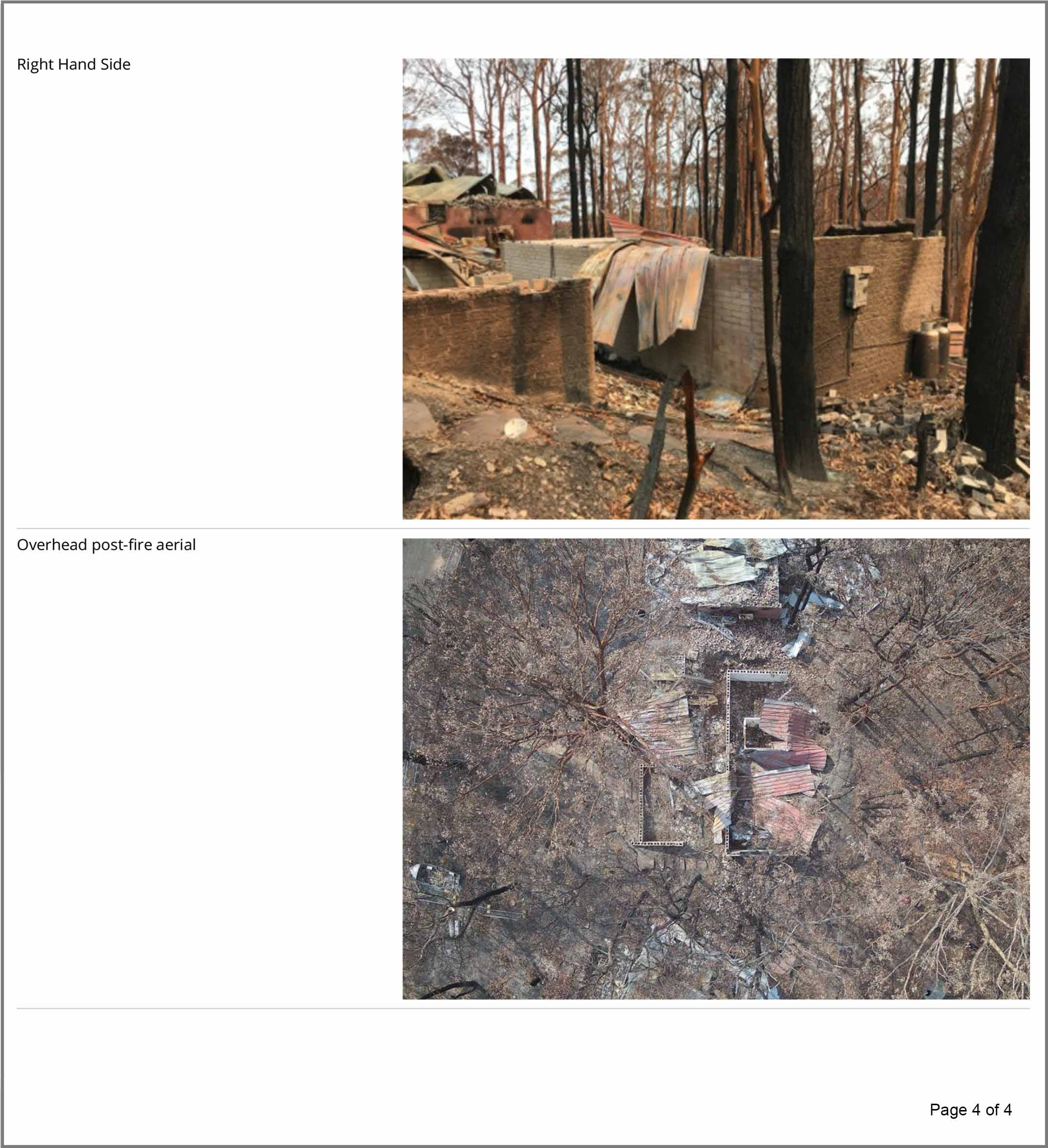

The FRNSW Bushfire and Aviation Unit produced models and orthomosaics of all sites with a GSD of 2-3cm, but found that linking ground and aerial data was critical for understanding what debris were being dealt with. To that end, the team created 200 individual property debris appraisal reports which included 360 degree post-impact photos, debris type triaging and before and after comparisons. Each report gives an indication of the types of waste found on the property.

Example fire damage report

Annotations made on Pix4Dcloud link individual buildings to the completed reports.

The consistent format of the reports made them easier to produce, and easier to communicate to local Councils and the Environmental Protection Authority of New South Wales.

What happens next

“At Fire and Rescue NSW, while we still fight fires and save people from burning buildings, we also do so much more than just respond. We do our very best every day to protect life and property but at the heart of it is best serving our communities and being prepared for anything that protects the irreplaceable,” says Tuinman-Neal.

“The team doesn't intend to stop there,” says Tuinman-Neal. “From the volume and debris data we collected about the different community debris profiles, we are going to extrapolate and generate a statewide baseline debris model. The hope is that in future, an initial debris impact model can be used as a baseline for recovery efforts. We see that at this point, the RPAS and data captured will be used to validate and further refine the model. This makes for a better prepared and efficient emergency recovery effort.”With the reports collated, waste can be safely cleared from the sites, and rebuilding can begin. “In this instance, we cannot undo the bushfire devastation, but we can provide the information that assists communities in taking that first step towards returning to some resemblance of normality,” says Tuinman-Neal.